Just got a short piece of CNF published at 10,000 Tons of Black Ink. My first "real" publishing credit.

Go here to read it: The Long Room

Thursday, December 3, 2009

Sunday, November 29, 2009

Holiday Giftbag: 5 Free Writing Tools

Just in time for the holidays: I decided to make a list of writing programs, tools, and resources that every writer should have.

The best part? Everything on this list is absolutely free. Go ahead. Give and give and give to yourself.

Let's get the good cheer a-rollin'.

The best part? Everything on this list is absolutely free. Go ahead. Give and give and give to yourself.

Let's get the good cheer a-rollin'.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

The Wonder Years: Great Short Story Writing

Over the weekend I went to see a friend perform at a local Chicago theater called "The Cornservatory," a very small theater (seats a maximum of about 40) that specializes in off-the-wall comedy. It's also BYOB: The last time I was there, I brought with me a bonafide cuisine of Pabst Blue Ribbon and Snickers. This time I opted for a sixer of Rolling Rock, skipping the candy bar.

Anyway, the show I saw was called "TV Reruns." The concept was simple: Five actors read scripts from actual episodes of campy (mostly 80s) TV shows like Alf, Small Wonder, and Murder, She Wrote, donning various wigs to play multiple roles. An off-stage narrator read the setting at the beginning of each scene (i.e. "in so-and-so's kitchen"), and the actors remained mostly stationary, aside from a few moments where they engaged in over-the-top physical tomfoolery to highlight each script's sublter moments.

A not-too-surprising truth was revealed to me as I listened to the actors read: television writing (especially in the 80s) is just awful. It's formulaic, predictable, and schmaltzy. That, of course, is why a comedic theater troupe decided to put on this show: the unintentional funny is everywhere. "TV Reruns" was engaging and entertaining for the simple fact that watching each reading was like witnessing a literary disaster unfold right before your eyes.

The first reading of the evening came from Doogie Howser, M.D., a show about a whiz kid who became a medical doctor (starring Neil Patrick Harris as Doogie). In the episode, Doogie is assigned by the hospital board to teach a high school sex education course, where he gets in a fight with the school jock (named "Swifty"). Of course, Doogie's mother is horrified when her son comes home with a black eye, while his father takes an unperturbed boys-will-be-boys approach to the matter. In the end, Swifty makes amends with Doogie when he consults Doogie about his too-swift sexual problem.

The second reading came from That 70s Show, which I found disappointing for the simple fact that it was much worse than I recalled. Eric gets suspended from school when he gets caught holding a cigarette that really belongs to his girlfriend Donna, which sets off Eric's father Red and pits him against Donna's father in a case of whose-child-is-a-worse-influence-on-whom. The rest of the episode is fluffed up with random hijinx from the relationship of Kelso and Jackie, as well as an oddball pairing of Hyde and Fez, who wind up on a double blind date with two co-eds.

During both of the above readings, I had little doubt in my mind that the performance I was watching, in which the actors on stage were performing a caricaturization of the original actors, was much funnier than the actual episode of either program. What was funny about each story was not the story itself, but rather the dreadfulness of each story.

But a funny thing happened during the third reading - an episode of The Wonder Years commonly known as the "Square Dancing" episode. About halfway through the reading, I realized that, instead of being engaged with the aforementioned literary disaster, I was engaged with the actual story. I was watching because I was invested in what was going to happen next. I was laughing because the story was actually funny, not because it was too dumb for words. By the end of the reading, I couldn't help but think of this episode of TWY not as a TV show, but as an expertly-crafted short story. (You can watch this almost-complete episode of TWY here, here, and here.) **Update: You can see the complete episode at Pandora. **

Of course, TWY uses an element common to prose storytelling: the first-person narrator. In this case, it is the voice of an older Kevin, looking back on his experiences as a teenager. This episode opens with panning shots of a yearbook as the narrator gives a brief introduction, which sounds not unlike something you'd read at the beginning of a short story or novel:

Right away, we are given a sense of the themes that the episode will cover - most notably, friendship, regret, and betrayal.

The opening scene sets up the major complication. Kevin's all-male seventh-grade gym class is informed that they will spend the next week learning to square dance. At first, the boys are incredulous at the idea, but quickly warm up once the girls' PE class is ushered in for pairing. Of course, Kevin's geeky best friend Paul lands the hottie, while Kevin gets stuck with the class weirdo: Margaret Farquhar (FAR-kwar).

This opening complication is little different from an opening scene in any other crappy formulaic sitcom. So why does it work? Part of it is due to the opening narration. We know that Margaret is not just some weird chick who will breeze into Kevin's life and be gone in thirty minutes. At some point, she will have a profound impact on him. The other part is due to the way that the rest of the episode is executed.

First of all, the writing doesn't rely merely on telling us that Margaret is weird ("Some people marched to the beat of a different drummer," Kevin's voiceover says, "Margaret had her own percussion section"), it also wastes no time in showing us exactly how weird she is, both to the other students and to the adults. Immediately after she is paired with Kevin, she begins asking the PE teachers questions in rapid-fire:

The next scene (which has unfortunately been edited out of the provided Youtube clip) takes place in the Arnolds' kitchen at dinnertime. After repeated teasings from the bully-older-brother Wayne, Kevin reveals to his family that he has been paired with Margaret for the week of square-dancing. Very cleverly, the writing hints at Margaret's epic reputation for weirdness when Kevin's older sister says, "Judy Farquhar's sister? She's a little different, isn't she?" But it is Kevin's who mom delivers the coup-de-grace. When Kevin, frustrated, says that he'll just find out a way to switch partners or "dump her," his mother intervenes: "Kevin, I expect more of you than that."

So, now we have Kevin being pulled in two different directions. If he is too nice to Margaret, he becomes a social pariah. If he is too mean, he will disappoint his mother. In fact, in subsequent scenes, the "I expected more from you than that" mantra is played in the voiceover, stopping Kevin at the last moment from saying something hurtful or doing something mean to Margaret. And it won't be easy for Kevin to achieve the balance between being nice and being too nice, as we see when Kevin and Margaret meet in the hallway during the following day at school:

Needless to say, we see Kevin's point. She really is weird. The writing doesn't merely rely on cliches (such as a strange voice or an oddball fashion sense - even if she does have a third pigtail) to showcase Margaret's weirdness. Her weirdness is just enough to put off any "normal" person, without being over-the-top or unbelievable. Later, she shows up at Kevin's house, toting a shoebox in which her pet bat Mortimer is hiding:

Two interesting things happen in this scene. First, the moral center of the story, Kevin's mom, can't even bring herself to stay in Margaret's presence very long. Second, during the last quick exchange between Margaret and Kevin, we are told something new: Margaret gets it. She knows that people don't like her. This adds a whole new dimension of self-awareness to Margaret's character that we never knew she had.

Shortly thereafter, in a very efficient, effective manner, the writing shows us exactly why Margaret is so weird:

And that's all you need to know about Margaret. This exchange reveals Margaret's inner-workings without over-explaining or leaving us pining for more information. It's a near-perfect reveal-of-character through dialogue.

So, now that we've covered the friendship, it's time to move on to betrayal. That night, Kevin loses his nerve on a promise he made to come over to Margaret's house and meet Isabelle, her tarantula. The next day at school, Kevin proposes an idea to Margaret: they can still be friends, but they won't talk to each other and no one will know that they are friends. Margaret becomes understandably upset, and a crowd gathers. This time, it is Margaret that delivers the coup-de-grace: "I thought you were different."

The line is ironic because it is essentially the same line that Kevin's mother used earlier ("I expected more out of you"), only phrased a bit differently.

Finally, regret. As Kevin and Margaret are shown engaging in a final day of joyless square-dancing:

Anyway, the show I saw was called "TV Reruns." The concept was simple: Five actors read scripts from actual episodes of campy (mostly 80s) TV shows like Alf, Small Wonder, and Murder, She Wrote, donning various wigs to play multiple roles. An off-stage narrator read the setting at the beginning of each scene (i.e. "in so-and-so's kitchen"), and the actors remained mostly stationary, aside from a few moments where they engaged in over-the-top physical tomfoolery to highlight each script's sublter moments.

A not-too-surprising truth was revealed to me as I listened to the actors read: television writing (especially in the 80s) is just awful. It's formulaic, predictable, and schmaltzy. That, of course, is why a comedic theater troupe decided to put on this show: the unintentional funny is everywhere. "TV Reruns" was engaging and entertaining for the simple fact that watching each reading was like witnessing a literary disaster unfold right before your eyes.

The first reading of the evening came from Doogie Howser, M.D., a show about a whiz kid who became a medical doctor (starring Neil Patrick Harris as Doogie). In the episode, Doogie is assigned by the hospital board to teach a high school sex education course, where he gets in a fight with the school jock (named "Swifty"). Of course, Doogie's mother is horrified when her son comes home with a black eye, while his father takes an unperturbed boys-will-be-boys approach to the matter. In the end, Swifty makes amends with Doogie when he consults Doogie about his too-swift sexual problem.

The second reading came from That 70s Show, which I found disappointing for the simple fact that it was much worse than I recalled. Eric gets suspended from school when he gets caught holding a cigarette that really belongs to his girlfriend Donna, which sets off Eric's father Red and pits him against Donna's father in a case of whose-child-is-a-worse-influence-on-whom. The rest of the episode is fluffed up with random hijinx from the relationship of Kelso and Jackie, as well as an oddball pairing of Hyde and Fez, who wind up on a double blind date with two co-eds.

During both of the above readings, I had little doubt in my mind that the performance I was watching, in which the actors on stage were performing a caricaturization of the original actors, was much funnier than the actual episode of either program. What was funny about each story was not the story itself, but rather the dreadfulness of each story.

But a funny thing happened during the third reading - an episode of The Wonder Years commonly known as the "Square Dancing" episode. About halfway through the reading, I realized that, instead of being engaged with the aforementioned literary disaster, I was engaged with the actual story. I was watching because I was invested in what was going to happen next. I was laughing because the story was actually funny, not because it was too dumb for words. By the end of the reading, I couldn't help but think of this episode of TWY not as a TV show, but as an expertly-crafted short story. (You can watch this almost-complete episode of TWY here, here, and here.) **Update: You can see the complete episode at Pandora. **

Of course, TWY uses an element common to prose storytelling: the first-person narrator. In this case, it is the voice of an older Kevin, looking back on his experiences as a teenager. This episode opens with panning shots of a yearbook as the narrator gives a brief introduction, which sounds not unlike something you'd read at the beginning of a short story or novel:

Kevin's VO: Some people pass through your life and you never think about them again. Some you think about and wonder whatever happened to them. . . Some you think about and wonder if they ever wonder whatever happened to you?

And then there are those you wish you never had to think about again. But you do.

Right away, we are given a sense of the themes that the episode will cover - most notably, friendship, regret, and betrayal.

The opening scene sets up the major complication. Kevin's all-male seventh-grade gym class is informed that they will spend the next week learning to square dance. At first, the boys are incredulous at the idea, but quickly warm up once the girls' PE class is ushered in for pairing. Of course, Kevin's geeky best friend Paul lands the hottie, while Kevin gets stuck with the class weirdo: Margaret Farquhar (FAR-kwar).

This opening complication is little different from an opening scene in any other crappy formulaic sitcom. So why does it work? Part of it is due to the opening narration. We know that Margaret is not just some weird chick who will breeze into Kevin's life and be gone in thirty minutes. At some point, she will have a profound impact on him. The other part is due to the way that the rest of the episode is executed.

First of all, the writing doesn't rely merely on telling us that Margaret is weird ("Some people marched to the beat of a different drummer," Kevin's voiceover says, "Margaret had her own percussion section"), it also wastes no time in showing us exactly how weird she is, both to the other students and to the adults. Immediately after she is paired with Kevin, she begins asking the PE teachers questions in rapid-fire:

Margaret: Are we gonna dosie-do?

Coach: We'll get to that.

Margaret: Why is it called dosie-do?

Coach: Because that's what it's called.

Margaret: Is that clockwise or the other way around?

The next scene (which has unfortunately been edited out of the provided Youtube clip) takes place in the Arnolds' kitchen at dinnertime. After repeated teasings from the bully-older-brother Wayne, Kevin reveals to his family that he has been paired with Margaret for the week of square-dancing. Very cleverly, the writing hints at Margaret's epic reputation for weirdness when Kevin's older sister says, "Judy Farquhar's sister? She's a little different, isn't she?" But it is Kevin's who mom delivers the coup-de-grace. When Kevin, frustrated, says that he'll just find out a way to switch partners or "dump her," his mother intervenes: "Kevin, I expect more of you than that."

So, now we have Kevin being pulled in two different directions. If he is too nice to Margaret, he becomes a social pariah. If he is too mean, he will disappoint his mother. In fact, in subsequent scenes, the "I expected more from you than that" mantra is played in the voiceover, stopping Kevin at the last moment from saying something hurtful or doing something mean to Margaret. And it won't be easy for Kevin to achieve the balance between being nice and being too nice, as we see when Kevin and Margaret meet in the hallway during the following day at school:

Margaret: Miss Billings sent me out here. She says I ask too many questions. Were you in the bathroom?

Kevin's VO: Great. I'd said three words to her, now we were going to have a whole conversation.

Margaret: I have to go a lot, too. When I drink to much water in the morning. Do you like bats?

Kevin: Bats?

Margaret: I have a fruit bat. Do you like the name Mortimer?

Needless to say, we see Kevin's point. She really is weird. The writing doesn't merely rely on cliches (such as a strange voice or an oddball fashion sense - even if she does have a third pigtail) to showcase Margaret's weirdness. Her weirdness is just enough to put off any "normal" person, without being over-the-top or unbelievable. Later, she shows up at Kevin's house, toting a shoebox in which her pet bat Mortimer is hiding:

Kevin's Mom: Is that Margaret?

Kevin's VO: Uh-oh, I could see mom's radar working overtime. In about three seconds, she was going to fall in love.

Kevin: She can't stay, mom.

Kevin's Mom: Now, I'm sure she can stay for a little while, can't you Margaret? Maybe she'd like to sit down.

Kevin's VO: That was it, Margaret was in like Flynn.

Margaret holds the box out to Kevin's mom.

Margaret: This is my bat!

Kevin's VO: But hold on, here.

Kevin's Mom: Bat?

Margaret: He won't go in your hair unless there's bugs there. I would have brought Isabelle, too, but her terrarium is too hard to carry.

Kevin's Mom: Isabelle?

Margaret: My tarantula. I also have a lizard, but he's sick.

Kevin's Mom: Oh. That's too bad. I hope he feels better.

Kevin's Mom exits.

Kevin's VO: Amazing. Mrs. Be-nice-to-everybody had been chased out of her own kitchen.

Margaret: I guess your mother doesn't like bats.

Kevin: No

Magaret: Yeah, neither does mine.

Two interesting things happen in this scene. First, the moral center of the story, Kevin's mom, can't even bring herself to stay in Margaret's presence very long. Second, during the last quick exchange between Margaret and Kevin, we are told something new: Margaret gets it. She knows that people don't like her. This adds a whole new dimension of self-awareness to Margaret's character that we never knew she had.

Shortly thereafter, in a very efficient, effective manner, the writing shows us exactly why Margaret is so weird:

Kevin's VO: And so I spent an hour with the most unpopular girl in school.

Margaret: Do you know where the word "tarantula" comes from?

Kevin: Huh.

Margaret: Well, they had this disease in Europe where if you got it, you would jerk around like you were dancing and they thought it came from spiders.

Kevin's VO: She was weird all right. The funny thing is, she was also interesting. In a weird way.

Margaret: So they named the spider after the dance. Taran-tella. Tarantula.

Kevin's VO: I'd never met anyone like her. Not that I liked her, you understand.

Kevin: So your dad was in the army?

Margaret: We travel a lot. Do you know anyone that's been to twelve schools in eight years?

Kevin: That's a lot of schools.

Margaret: Bats are good travelers. Dogs you have to leave behind.

And that's all you need to know about Margaret. This exchange reveals Margaret's inner-workings without over-explaining or leaving us pining for more information. It's a near-perfect reveal-of-character through dialogue.

So, now that we've covered the friendship, it's time to move on to betrayal. That night, Kevin loses his nerve on a promise he made to come over to Margaret's house and meet Isabelle, her tarantula. The next day at school, Kevin proposes an idea to Margaret: they can still be friends, but they won't talk to each other and no one will know that they are friends. Margaret becomes understandably upset, and a crowd gathers. This time, it is Margaret that delivers the coup-de-grace: "I thought you were different."

The line is ironic because it is essentially the same line that Kevin's mother used earlier ("I expected more out of you"), only phrased a bit differently.

Finally, regret. As Kevin and Margaret are shown engaging in a final day of joyless square-dancing:

Kevin's VO: And so, that last day of square-dancing, I danced alone.Now how many sitcoms - especially in the 80s, of all god-forsaken decades - had all of that in one episode? How many short stories have you read recently that had all of that? Shit, how many novels have you read that had all of that?

Maybe if I'd been a little braver, I could have been her friend, but the truth is, in seventh grade, who you are is what other seventh-graders say you are.

The funny thing is, it's hard to remember the names of the kids you spent so much time trying to impress. But you don't forget someone like Margaret Farquhar. Professor of Biology. Mother of six. Friend to bats.

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Keep Your Awesome To Yourself

I really enjoy attending readings. Sure, sometimes it can be painful - some (maybe even the majority) of authors are simply not good public speakers. Their lack of a powerful oratory presence is probably one of the reasons they've chosen to be writers in the first place. This is not a finger-pointing criticism; I've given a couple readings before, and believe me - it's hard.

But the reason I really enjoy attending readings is that I always learn something. I might discover the work of an author I wouldn't otherwise have found, or some interesting use of language might catch my attention, or I might just learn how to become a better public reader myself.

Earlier this week, I attended a reading given by four local authors. On this occasion, I learned something from an author who, strangely enough, didn't read anything at all.

(Note: I'll refer to this particular author as "he/him," although this may or may not reflect the actual gender of the author in question.)

The author in question was the evening's feature author, the last of the four local authors to read. His next book (the newest edition of a somewhat popular historical fiction series that I hadn't heard of before) was coming out soon, and he began by explaining that he was so tired of his own words that, in lieu of reading, he would give a brief talk about how he became a working writer.

I was slightly put off by this introduction. After all, all the authors that evening were probably more or less tired of their words, but they read them anyway. Furthermore, his complaint of being exhausted over his own soon-to-be-published novel in the presence of a literary-minded crowd - many of whom were no doubt fledgling writers themselves - made him look more than a little out-of-touch. (The words "let them eat cake" kept echoing in my mind as he spoke.)

But I decided I was being petty: the setting at this particular reading was informal and intimate, so certainly he was not receiving any monetary compensation for appearing, and therefore he retained the right to read or not read whatever he wanted. Also, at any reading, there are a collection of wannabe writers (such as myself) who want to learn more about the publishing industry. Maybe, I thought, he could teach me something I didn't know.

Unfortunately, his story contained few surprises. He began with the all-too familiar you-can-do-it motivational speech for writers: For years, he talked about becoming a writer. He talked and talked and talked about it, told everyone who asked him about his work and interests. Then one day his three-year-old asked him why he always lied to people about being a writer. So that lit a fire under his ass and he wrote and wrote and wrote. The story ended with an oh-shucks-my-first-query-letter-hit success tale. Now, he writes for a living. He achieved the holy grail: living as a gainfully employed, full-time writer.

At its core, I found no particular fault in this little speech. He put in the work and became successful, good for him. I would have been fine with everything if this writer had been reading alone, or if he had read with other writers at the same or greater level of success than his own. But what pushed the whole ordeal into the realm of bad taste was the fact that this writer was reading with people who had been published at small presses, who still worked regular full-time jobs, and at least one writer who had self-published her book. Again, the utter lack of situational awareness certainly didn't win her any new fans that evening.

During the Q&A, one person asked the author who self-published whether or not she'd do it again. Her response began: "Well, I didn't have the magic fairy dust that so-and-so had...." The comment was made in jest, and a good-natured chuckle spread through the room, but I sensed just a bit of uneasiness in the successful writer's smile, as if he finally understood the mistake he had made.

The lesson to be learned: If you're asked to read your work, just read it. Even if you're genuinely impressed with your own success, it's faulty to believe that anyone else will want to hear about it.

But the reason I really enjoy attending readings is that I always learn something. I might discover the work of an author I wouldn't otherwise have found, or some interesting use of language might catch my attention, or I might just learn how to become a better public reader myself.

Earlier this week, I attended a reading given by four local authors. On this occasion, I learned something from an author who, strangely enough, didn't read anything at all.

(Note: I'll refer to this particular author as "he/him," although this may or may not reflect the actual gender of the author in question.)

The author in question was the evening's feature author, the last of the four local authors to read. His next book (the newest edition of a somewhat popular historical fiction series that I hadn't heard of before) was coming out soon, and he began by explaining that he was so tired of his own words that, in lieu of reading, he would give a brief talk about how he became a working writer.

I was slightly put off by this introduction. After all, all the authors that evening were probably more or less tired of their words, but they read them anyway. Furthermore, his complaint of being exhausted over his own soon-to-be-published novel in the presence of a literary-minded crowd - many of whom were no doubt fledgling writers themselves - made him look more than a little out-of-touch. (The words "let them eat cake" kept echoing in my mind as he spoke.)

But I decided I was being petty: the setting at this particular reading was informal and intimate, so certainly he was not receiving any monetary compensation for appearing, and therefore he retained the right to read or not read whatever he wanted. Also, at any reading, there are a collection of wannabe writers (such as myself) who want to learn more about the publishing industry. Maybe, I thought, he could teach me something I didn't know.

Unfortunately, his story contained few surprises. He began with the all-too familiar you-can-do-it motivational speech for writers: For years, he talked about becoming a writer. He talked and talked and talked about it, told everyone who asked him about his work and interests. Then one day his three-year-old asked him why he always lied to people about being a writer. So that lit a fire under his ass and he wrote and wrote and wrote. The story ended with an oh-shucks-my-first-query-letter-hit success tale. Now, he writes for a living. He achieved the holy grail: living as a gainfully employed, full-time writer.

At its core, I found no particular fault in this little speech. He put in the work and became successful, good for him. I would have been fine with everything if this writer had been reading alone, or if he had read with other writers at the same or greater level of success than his own. But what pushed the whole ordeal into the realm of bad taste was the fact that this writer was reading with people who had been published at small presses, who still worked regular full-time jobs, and at least one writer who had self-published her book. Again, the utter lack of situational awareness certainly didn't win her any new fans that evening.

During the Q&A, one person asked the author who self-published whether or not she'd do it again. Her response began: "Well, I didn't have the magic fairy dust that so-and-so had...." The comment was made in jest, and a good-natured chuckle spread through the room, but I sensed just a bit of uneasiness in the successful writer's smile, as if he finally understood the mistake he had made.

The lesson to be learned: If you're asked to read your work, just read it. Even if you're genuinely impressed with your own success, it's faulty to believe that anyone else will want to hear about it.

Sunday, August 2, 2009

An Old Man's Plea

This past Thursday, I received news that a former Northwestern classmate of mine had been killed by a drunk driver. NU Senior Corrie Lazar was walking along a road in Maine, where she was spending the summer as an arts-and-crafts camp counselor, when she was struck by a SUV that had veered off the road.

I was not close with Corrie. I shared only one class with her, during my last quarter at NU, and I only spoke with her a handful of times. The only interaction that I can recall with clarity was the time she wore a green hoodie to class that read "Ithaca is Gorges." I told her there should be more puns on sweatshirts. She agreed.

Still, I have spent the majority of the weekend feeling unwell, like there's a perfectly round stone lodged in my stomach just above my bellybutton. I won't say that I feel traumatized by what happened - that would be insulting to those who were truly close to Corrie. But there is definitely a deep sadness, to the point where I have found it quite difficult to concentrate on anything over the last few days. I have been somewhat perplexed by this wave of emotion. Corrie is not the first young person with whom I have been personally acquainted who has died in recent years; yet, I do not recall feeling this kind of lasting impact on any of those previous occasions.

I think there are a number of reasons that I have been feeling this way, first and foremost the simple fact that what happened to Corrie is completely unacceptable. It could also have something to do with the fact that all those young acquaintances of mine that have died have been men; Corrie is the first young woman that I have known personally who has died. Maybe I naturally have more empathy for women.

But I think there's another part of it as well, and it has to do with my age. I apologize in advance to those NU friends of mine who have no doubt heard me give more than one "old man" speech in my time. It's a tired spiel, but I ask you to please endure it one more time.

Corrie had just turned 21. She was nearly 5 years younger than myself. The last five years of my life haven't been all roses and sunshine, but I'm certainly happy to have endured it all. It's been far and away the best five-year stretch of my life, largely because of the people I've become friends with at Northwestern. When I first got to Northwestern, you young ambitious kids scared the shit out of me. I really did feel old; but not because I felt any more mature or any wiser. On the contrary, I felt old because, compared to the rest of you, I felt I had wasted a lot of time. I felt I had acted immaturely in comparison. Before I arrived at Northwestern, I didn't think they made 18- and 19-year-olds as bright and hard-working as the lot of you.

So, I'm sure that, for a while, I was bitter and resentful of all of you. But I got over it, thankfully. I found my niche, made some friends, and considered myself lucky to be learning alongside you.

And that's why, as my years at Northwestern went by, my respect for you spawned a keen sense of protectiveness. It literally makes me weak in the knees to think of harm coming to any of you. There's just too much goddamn potential to be lost, certainly more potential than I have ever had or ever will. That's what makes me feel so awful about Corrie's death - that there's somebody that's infinitely smarter, more ambitious, and harder-working than I'll ever be - and she's being cheated out of the five years that I have had, and more.

So to all my friends, but especially to those NU friends who are just now getting out into the "real world," who are now beyond the places where I can keep a watchful eye on you, I say: please, please, be safe. If you are not safe, you will break this old man's heart.

If you would like to make a donation in Corrie's honor to Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), visit http://www.madd.org/Donate.aspx, click on "Memorial," and write "Corrie Lazar" into the text box.

I was not close with Corrie. I shared only one class with her, during my last quarter at NU, and I only spoke with her a handful of times. The only interaction that I can recall with clarity was the time she wore a green hoodie to class that read "Ithaca is Gorges." I told her there should be more puns on sweatshirts. She agreed.

Still, I have spent the majority of the weekend feeling unwell, like there's a perfectly round stone lodged in my stomach just above my bellybutton. I won't say that I feel traumatized by what happened - that would be insulting to those who were truly close to Corrie. But there is definitely a deep sadness, to the point where I have found it quite difficult to concentrate on anything over the last few days. I have been somewhat perplexed by this wave of emotion. Corrie is not the first young person with whom I have been personally acquainted who has died in recent years; yet, I do not recall feeling this kind of lasting impact on any of those previous occasions.

I think there are a number of reasons that I have been feeling this way, first and foremost the simple fact that what happened to Corrie is completely unacceptable. It could also have something to do with the fact that all those young acquaintances of mine that have died have been men; Corrie is the first young woman that I have known personally who has died. Maybe I naturally have more empathy for women.

But I think there's another part of it as well, and it has to do with my age. I apologize in advance to those NU friends of mine who have no doubt heard me give more than one "old man" speech in my time. It's a tired spiel, but I ask you to please endure it one more time.

Corrie had just turned 21. She was nearly 5 years younger than myself. The last five years of my life haven't been all roses and sunshine, but I'm certainly happy to have endured it all. It's been far and away the best five-year stretch of my life, largely because of the people I've become friends with at Northwestern. When I first got to Northwestern, you young ambitious kids scared the shit out of me. I really did feel old; but not because I felt any more mature or any wiser. On the contrary, I felt old because, compared to the rest of you, I felt I had wasted a lot of time. I felt I had acted immaturely in comparison. Before I arrived at Northwestern, I didn't think they made 18- and 19-year-olds as bright and hard-working as the lot of you.

So, I'm sure that, for a while, I was bitter and resentful of all of you. But I got over it, thankfully. I found my niche, made some friends, and considered myself lucky to be learning alongside you.

And that's why, as my years at Northwestern went by, my respect for you spawned a keen sense of protectiveness. It literally makes me weak in the knees to think of harm coming to any of you. There's just too much goddamn potential to be lost, certainly more potential than I have ever had or ever will. That's what makes me feel so awful about Corrie's death - that there's somebody that's infinitely smarter, more ambitious, and harder-working than I'll ever be - and she's being cheated out of the five years that I have had, and more.

So to all my friends, but especially to those NU friends who are just now getting out into the "real world," who are now beyond the places where I can keep a watchful eye on you, I say: please, please, be safe. If you are not safe, you will break this old man's heart.

If you would like to make a donation in Corrie's honor to Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), visit http://www.madd.org/Donate.aspx, click on "Memorial," and write "Corrie Lazar" into the text box.

Tuesday, July 7, 2009

A Life in Odd Jobs

At the age of 25, after insisting time and again that a lot of people go to college for seven years, I finally graduated a couple weeks ago.

Since then, of course, I've been on the great job hunt. For a guy with a degree in Creative Writing in this economy, I have to say I'm somewhat pleased with my prospects so far. It could be much, much worse.

While working on my resume and cover letters, I've had to spend a lot of time thinking about my old jobs, and how I can work that prior experience into a line of cover-letter-bullshit just clever enough to fool a prospective employer into thinking that I know what I'm doing. It's really the ultimate practical form of creative non-fiction.

The thing is, I've had a lot of jobs. I doubt there's very many people at my age who have held as many jobs as I have. I like to think of it as a mediocre badge of honor. I've had so many jobs now that it's hard to keep track of all of them in my head. In fact, about three jobs ago, I had to undergo a full background check, and part of that was providing them with the phone numbers and addresses of all my previous employers. Simply getting all that information together took a good week.

Anyway, here's a list of the jobs I've had, starting at the age of 16:

1. Stock Clerk, Osco Drug

2. Inventory Dude, RGIS

3. Video Store Clerk/Manager, Moore Movies (mom-and-pop place)

4. Production Assistant, City Channel 4 (Iowa City)

5. Camera Op/Deko Operator, small-market CBS affiliate (Cedar Rapids)

6. Cafe Manager, Borders Books

7. Banker, Mohegan Sun Casino

8. Bartender, Cafe Luciano (small Italian restaurant in Evanston)

9. Content Developer, CognitiveArts

And I still feel like I'm missing something. I've only held two of these jobs for longer than a year (#1, #3), and I've never been fired.

The worst job: DEFINITELY job #2, the inventory specialist gig for RGIS. Let me tell you how this job went. You were given a scanner gun to scan UPC bars, which connected to this giant 1970s calculator-looking thing on your hip. You'd go as a team into a retail store (either before the store opened or after they closed, so the hours were always god-awful), let's say a Kohl's, and you'd go to a rack of clothes, push the clothes to the back of the rack, then pull the first garment forward and scan. Pull the next garment forward and scan. Repeat until every item in the whole damn store was scanned. Just the most god-awful, mind-numbing brain torture you can put yourself through.

An honorable mention goes to the Cafe Manager job at Borders. I only did it for about a month. I basically walked into a chaotic situation. I learned later that the three managers before me had abruptly quit, which caused a certain amount of mayhem, and a failed health inspection shortly before my arrival. I don't even drink coffee, so I sure as hell had no interest in fixing all of their problems.

The easiest job: Store manager of Moore Movies. Man, I did a LOT of reading during my time at Moore Movies. Basically, they just needed someone to be there and man the cash register. During the day, that was usually me. So I'd come in, have about 30 minutes worth of actual managerial work to do, and then sit on my ass the rest of the day. You know when you walk into a store, and see a guy that's doing absolutely nothing, so you say to your friends, "Boy, I'd like to have that guy's job [Possibly not-work-safe]." Well, I was that guy.

The best job: It's a toss-up betweent the Bartender gig and the Content Developer gig. Being a content developer was my first "real" job, so it was nice, on the ninth try, to finally get it right. Plus, it was a writing job, albeit rather boring (at times) corporate writing. But bartending was a lot of fun, and the place was small, so I got to know a lot of regulars. It also paid a lot better than the TV gigs, and didn't crush my soul in the same way that working in TV News did. (For an experiment: watch the same 30-minute news program five times each day for about 6 months, and you will understand why I nearly turned into this.) The only problem was that the restaurant wasn't busy enough, as they ended up closing it down one day without informing me. Bummer.

There's kind of a strange creative non-fiction thing that happens when I think about each one of these jobs individually. I know I did them, but I think about them as if it must have been somebody else doing them. This probably has something to do with the fact that the earliest jobs came as much as a decade ago, but it also has to do with the fact that each one of these jobs brought out a different person in me. They also took place in geographically different places (Aurora, Iowa, Connecticut, Chicago) and at different stages of my early adulthood (high school, community college, I'm-ruining-my-life, and I-decided-to-get-my-act-together-and-go-to-Northwestern). For example, the Osco-Drug me is the high school me who made friends with as many co-workers as he could manage. The Mohegan Sun me is the extremely introverted me who became jaded at the sight of millions of dollars cash every day. The content developer me is the me who really winged it in order to not screw up probably the best professional opportunity I had ever had. And none of them seem like actually me. It's similar to the way you feel about two days after returning home from vacation. You know you did all that fun stuff in a foreign place, but did you really? Or was it someone else?

Perhaps the strangest point of all this, though, is that even though all of these jobs had their own odd quirks and characters, I have never written about any of them - non-fiction, fiction, or poetry - until now in my cover letters. And the only one I really write about in the cover letters is the last one, because that's the most relevant to the jobs I am pursuing.

So my (very long-winded) question is three-parted:

Should I write about my old jobs (in a creative piece)?

Which one(s) would you want to hear about?

Which medium (fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry)?

Since then, of course, I've been on the great job hunt. For a guy with a degree in Creative Writing in this economy, I have to say I'm somewhat pleased with my prospects so far. It could be much, much worse.

While working on my resume and cover letters, I've had to spend a lot of time thinking about my old jobs, and how I can work that prior experience into a line of cover-letter-bullshit just clever enough to fool a prospective employer into thinking that I know what I'm doing. It's really the ultimate practical form of creative non-fiction.

The thing is, I've had a lot of jobs. I doubt there's very many people at my age who have held as many jobs as I have. I like to think of it as a mediocre badge of honor. I've had so many jobs now that it's hard to keep track of all of them in my head. In fact, about three jobs ago, I had to undergo a full background check, and part of that was providing them with the phone numbers and addresses of all my previous employers. Simply getting all that information together took a good week.

Anyway, here's a list of the jobs I've had, starting at the age of 16:

1. Stock Clerk, Osco Drug

2. Inventory Dude, RGIS

3. Video Store Clerk/Manager, Moore Movies (mom-and-pop place)

4. Production Assistant, City Channel 4 (Iowa City)

5. Camera Op/Deko Operator, small-market CBS affiliate (Cedar Rapids)

6. Cafe Manager, Borders Books

7. Banker, Mohegan Sun Casino

8. Bartender, Cafe Luciano (small Italian restaurant in Evanston)

9. Content Developer, CognitiveArts

And I still feel like I'm missing something. I've only held two of these jobs for longer than a year (#1, #3), and I've never been fired.

The worst job: DEFINITELY job #2, the inventory specialist gig for RGIS. Let me tell you how this job went. You were given a scanner gun to scan UPC bars, which connected to this giant 1970s calculator-looking thing on your hip. You'd go as a team into a retail store (either before the store opened or after they closed, so the hours were always god-awful), let's say a Kohl's, and you'd go to a rack of clothes, push the clothes to the back of the rack, then pull the first garment forward and scan. Pull the next garment forward and scan. Repeat until every item in the whole damn store was scanned. Just the most god-awful, mind-numbing brain torture you can put yourself through.

An honorable mention goes to the Cafe Manager job at Borders. I only did it for about a month. I basically walked into a chaotic situation. I learned later that the three managers before me had abruptly quit, which caused a certain amount of mayhem, and a failed health inspection shortly before my arrival. I don't even drink coffee, so I sure as hell had no interest in fixing all of their problems.

The easiest job: Store manager of Moore Movies. Man, I did a LOT of reading during my time at Moore Movies. Basically, they just needed someone to be there and man the cash register. During the day, that was usually me. So I'd come in, have about 30 minutes worth of actual managerial work to do, and then sit on my ass the rest of the day. You know when you walk into a store, and see a guy that's doing absolutely nothing, so you say to your friends, "Boy, I'd like to have that guy's job [Possibly not-work-safe]." Well, I was that guy.

The best job: It's a toss-up betweent the Bartender gig and the Content Developer gig. Being a content developer was my first "real" job, so it was nice, on the ninth try, to finally get it right. Plus, it was a writing job, albeit rather boring (at times) corporate writing. But bartending was a lot of fun, and the place was small, so I got to know a lot of regulars. It also paid a lot better than the TV gigs, and didn't crush my soul in the same way that working in TV News did. (For an experiment: watch the same 30-minute news program five times each day for about 6 months, and you will understand why I nearly turned into this.) The only problem was that the restaurant wasn't busy enough, as they ended up closing it down one day without informing me. Bummer.

There's kind of a strange creative non-fiction thing that happens when I think about each one of these jobs individually. I know I did them, but I think about them as if it must have been somebody else doing them. This probably has something to do with the fact that the earliest jobs came as much as a decade ago, but it also has to do with the fact that each one of these jobs brought out a different person in me. They also took place in geographically different places (Aurora, Iowa, Connecticut, Chicago) and at different stages of my early adulthood (high school, community college, I'm-ruining-my-life, and I-decided-to-get-my-act-together-and-go-to-Northwestern). For example, the Osco-Drug me is the high school me who made friends with as many co-workers as he could manage. The Mohegan Sun me is the extremely introverted me who became jaded at the sight of millions of dollars cash every day. The content developer me is the me who really winged it in order to not screw up probably the best professional opportunity I had ever had. And none of them seem like actually me. It's similar to the way you feel about two days after returning home from vacation. You know you did all that fun stuff in a foreign place, but did you really? Or was it someone else?

Perhaps the strangest point of all this, though, is that even though all of these jobs had their own odd quirks and characters, I have never written about any of them - non-fiction, fiction, or poetry - until now in my cover letters. And the only one I really write about in the cover letters is the last one, because that's the most relevant to the jobs I am pursuing.

So my (very long-winded) question is three-parted:

Should I write about my old jobs (in a creative piece)?

Which one(s) would you want to hear about?

Which medium (fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry)?

Wednesday, July 1, 2009

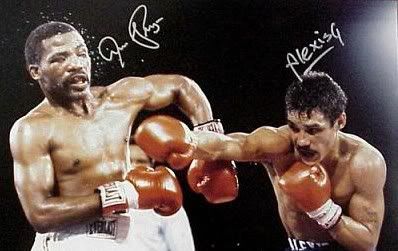

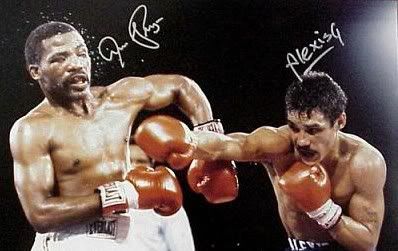

Alexis Arguello (1952-2009)

Former featherweight, superfeatherweight, and lightweight champion of the world Alexis Arguello was found dead in his home in Nicaragua this morning, after he apparently shot himself in the chest.

The majority of Arguello's career took place before I was born, and long before I became a fan of boxing only a handful of years ago. Nonetheless, I have watched a number of his fights on video, either on ESPN Classic or on Youtube, and have been a fan of him ever since I watched my first Arguello fight.

When I think of Arguello as he was in the ring, it makes the circumstances of his death (an apparent suicide) extremely hard to comprehend. Inside the boxing ring, there has never been an individual who displayed more professionalism and class than Alexis Arguello, both in the way that he fought and in the way that he carried himself before and after a fight.

Before a fight, Arguello was calm, quiet, and collected, seemingly immune to the nervous, bouncy energy of so many fighters in the moments before the opening bell. During the fight, Arguello never showed emotion, never became rattled when his opponent put pressure on him, never lost his footing, never found himself in a position where he couldn't, at any moment, unload a devastating blow. And after the fight, most of which ended with his opponent on the canvas (65 of his 82 career victories ended in knockouts), he was often the first to his opponent's side, congratulating him and his cornermen on a valiant fight. (For two examples, fast forward to about 3:00 of the first video below.)

His road to stardom was unusual by boxing standards. For starters, he lost his first professional fight in 1968, and then his fifth, before winning 23 of his next 24. In 1974, he had his first fight for a world championship (featherweight), and lost, but came back to win the title nine months later. In 1978, after a number of successful defenses of his title, Arguello moved up to super featherweight and won that world title. In 1981, he moved up again, winning the lightweight world championship. That made Arguello only the sixth man in boxing history to own world championships in three different weight divisions. (On top of everything, he became a political exile of his native Nicaragua after the Sandinistas took power in the late 70s, after a complicated dispute that I won't get into here, but you can feel free to research if you'd like.)

Arguello tested history one more time in 1982, when he tried to become the first man ever to own championships in four different weightclasses by fighting Aaron Pryor, the undefeated light welterweight champion. The fight went down as one of the best epic battles in boxing history (which you can see here, here, here, here, and here). In an all-action fight from the opening bell, Arguello stole the momentum in the middle rounds, scoring one particularly nasty right hand on Pryor, which he later said he expected to end the fight, cocking Pryor's head straight back until he could see the stadium lights. Pryor made it through the round, fighting on, and unleashed a barrage of punches on Arguello in round 14, forcing referree Stanley Christodoulou to stop the fight.

The last significant fight of Arguello's career came a year later, when he again fought Pryor for the light welterweight title, this time losing by stoppage in the tenth round. The younger, faster, bigger Pryor (an all-time great in his own right) simply proved too much for Arguello, a man then past his 80th professional fight.

In his retirement, Arguello faced the kind of demons that many fighters do - namely, alcohol and drugs. At times, he spoke openly of having suicidal thoughts. Recent years had seemingly brought some peace to Arguello. He became mayor of his native city Managua, the capitol city of Nicaragua, in 2004. More recently, he was the honorary Nicaraguan flag-bearer during the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing.

Every time I see a cocky young boxer (or MMA-guy) these days, I think about what would happen if they had to look across the ring at Alexis Arguello. More than likely, they'd absolutely piss themselves. For a nice guy, he must have been downright frightening to face.

As one close friend said about Arguello: "He was one of those champions who acted like one outside the ring. You don't hardly see those kind of fighters around today."

He was a bad, bad man. But a true gentleman at heart.

The majority of Arguello's career took place before I was born, and long before I became a fan of boxing only a handful of years ago. Nonetheless, I have watched a number of his fights on video, either on ESPN Classic or on Youtube, and have been a fan of him ever since I watched my first Arguello fight.

When I think of Arguello as he was in the ring, it makes the circumstances of his death (an apparent suicide) extremely hard to comprehend. Inside the boxing ring, there has never been an individual who displayed more professionalism and class than Alexis Arguello, both in the way that he fought and in the way that he carried himself before and after a fight.

Before a fight, Arguello was calm, quiet, and collected, seemingly immune to the nervous, bouncy energy of so many fighters in the moments before the opening bell. During the fight, Arguello never showed emotion, never became rattled when his opponent put pressure on him, never lost his footing, never found himself in a position where he couldn't, at any moment, unload a devastating blow. And after the fight, most of which ended with his opponent on the canvas (65 of his 82 career victories ended in knockouts), he was often the first to his opponent's side, congratulating him and his cornermen on a valiant fight. (For two examples, fast forward to about 3:00 of the first video below.)

His road to stardom was unusual by boxing standards. For starters, he lost his first professional fight in 1968, and then his fifth, before winning 23 of his next 24. In 1974, he had his first fight for a world championship (featherweight), and lost, but came back to win the title nine months later. In 1978, after a number of successful defenses of his title, Arguello moved up to super featherweight and won that world title. In 1981, he moved up again, winning the lightweight world championship. That made Arguello only the sixth man in boxing history to own world championships in three different weight divisions. (On top of everything, he became a political exile of his native Nicaragua after the Sandinistas took power in the late 70s, after a complicated dispute that I won't get into here, but you can feel free to research if you'd like.)

Arguello tested history one more time in 1982, when he tried to become the first man ever to own championships in four different weightclasses by fighting Aaron Pryor, the undefeated light welterweight champion. The fight went down as one of the best epic battles in boxing history (which you can see here, here, here, here, and here). In an all-action fight from the opening bell, Arguello stole the momentum in the middle rounds, scoring one particularly nasty right hand on Pryor, which he later said he expected to end the fight, cocking Pryor's head straight back until he could see the stadium lights. Pryor made it through the round, fighting on, and unleashed a barrage of punches on Arguello in round 14, forcing referree Stanley Christodoulou to stop the fight.

The last significant fight of Arguello's career came a year later, when he again fought Pryor for the light welterweight title, this time losing by stoppage in the tenth round. The younger, faster, bigger Pryor (an all-time great in his own right) simply proved too much for Arguello, a man then past his 80th professional fight.

In his retirement, Arguello faced the kind of demons that many fighters do - namely, alcohol and drugs. At times, he spoke openly of having suicidal thoughts. Recent years had seemingly brought some peace to Arguello. He became mayor of his native city Managua, the capitol city of Nicaragua, in 2004. More recently, he was the honorary Nicaraguan flag-bearer during the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing.

Every time I see a cocky young boxer (or MMA-guy) these days, I think about what would happen if they had to look across the ring at Alexis Arguello. More than likely, they'd absolutely piss themselves. For a nice guy, he must have been downright frightening to face.

As one close friend said about Arguello: "He was one of those champions who acted like one outside the ring. You don't hardly see those kind of fighters around today."

He was a bad, bad man. But a true gentleman at heart.

Wednesday, June 10, 2009

On Documenting Ourselves

Last week, I traveled to Upper Michigan for my grandmother's (mother's side) funeral. She was 95 years old. A little over a year ago, my other grandmother died of Alzheimer's; she had lived (I think) to 87 years. There's some long-life genes floating around my family.

My brother, my parents, and I stayed the night at the house of my grandfather (father's side) - now my only livng grandparent - who was not at home because he was being kept at the nursing home for a few weeks following complications in the wake of a bad infection and surgery. It was a tough week for grandparents.

In an extra room of the house, my brother found a few grocery bags full of old photographs and documents from the 1920s, 30s, 40s, and 50s. My dad sat with my brother and I late one night and identified the people that he could: uncles, aunts, cousins; his own mother, no older than 8 years old, standing on a forest clearing in front of an old Studebaker or some other old car; himself, at a beach, perhaps five years old, with two of my uncles and our grandfather, probably not much older than myself. There were some old documents in the bag as well, including the high school report cards for both my grandmother and grandfather, and my grandmother's nursing school report card. (One of the comments written on the card said something to the effect of: "Has acne but pleasant personality.")

I couldn't help but think how unbelievably precious all these pictures and documents were; I don't mean precious in the sense of cute, but precious in the sense that most of the items in those bags were the only existing copies, the originals themselves. I felt grateful that someone had thought to keep them, to put them into these bags instead of throwing it all away, if for no other purpose than to be found and looked over on this one evening by my father, brother, and myself. I only wished that it were a more complete record.

Of course, part of the bitterness of the funerals of relatives is that they always serve as a reminder of our own mortality. I couldn't help but think about how our own children and grandchildren will cycle through our own photos from our youths. We document ourselves so thoroughly these days, the records of ourselves exist in electronic data. When our grandchildren want to remember us, will they look through our Facebook profiles, which by then we will have kept updated for decades? The thought of that disgusted me. Won't the glut of documentations of ourselves cheapen the memories of us? Or will our children and grandchildren be grateful that they have such a thorough documentation of us? Will they too, after the endless blog entries and the thousands of pictures and the podcasts and tumblers and twitters and whatever, wish they had more?

I suppose it's better to err on the side of over-documenting ourselves than under-documenting ourselves. Historians never wish that they had less record of an ancient people.

This might seem out of left field, but I recently saw a great documentary about Hurricane Katrina called Trouble the Water. The filmmakers met a couple from the ninth ward of New Orleans - the poor area of town that was hit hardest by the hurricane, and still lies mostly in ruin. This couple had videotaped their experience of making it through the storm itself (they had no car and could not evacuate). The first 15 minutes of Trouble the Water is cut together from this high-8 videotape footage. As I watched this sequence, I couldn't help but think "Thank God someone documented this." As much as I want to err on the side of having too much documentation, there is something wonderful about knowing that you are witnessing the only account of something, that you are holding, in your hand, the only photograph of that moment in time. There is something satisfying about having very little.

My brother, my parents, and I stayed the night at the house of my grandfather (father's side) - now my only livng grandparent - who was not at home because he was being kept at the nursing home for a few weeks following complications in the wake of a bad infection and surgery. It was a tough week for grandparents.

In an extra room of the house, my brother found a few grocery bags full of old photographs and documents from the 1920s, 30s, 40s, and 50s. My dad sat with my brother and I late one night and identified the people that he could: uncles, aunts, cousins; his own mother, no older than 8 years old, standing on a forest clearing in front of an old Studebaker or some other old car; himself, at a beach, perhaps five years old, with two of my uncles and our grandfather, probably not much older than myself. There were some old documents in the bag as well, including the high school report cards for both my grandmother and grandfather, and my grandmother's nursing school report card. (One of the comments written on the card said something to the effect of: "Has acne but pleasant personality.")

I couldn't help but think how unbelievably precious all these pictures and documents were; I don't mean precious in the sense of cute, but precious in the sense that most of the items in those bags were the only existing copies, the originals themselves. I felt grateful that someone had thought to keep them, to put them into these bags instead of throwing it all away, if for no other purpose than to be found and looked over on this one evening by my father, brother, and myself. I only wished that it were a more complete record.

Of course, part of the bitterness of the funerals of relatives is that they always serve as a reminder of our own mortality. I couldn't help but think about how our own children and grandchildren will cycle through our own photos from our youths. We document ourselves so thoroughly these days, the records of ourselves exist in electronic data. When our grandchildren want to remember us, will they look through our Facebook profiles, which by then we will have kept updated for decades? The thought of that disgusted me. Won't the glut of documentations of ourselves cheapen the memories of us? Or will our children and grandchildren be grateful that they have such a thorough documentation of us? Will they too, after the endless blog entries and the thousands of pictures and the podcasts and tumblers and twitters and whatever, wish they had more?

I suppose it's better to err on the side of over-documenting ourselves than under-documenting ourselves. Historians never wish that they had less record of an ancient people.

This might seem out of left field, but I recently saw a great documentary about Hurricane Katrina called Trouble the Water. The filmmakers met a couple from the ninth ward of New Orleans - the poor area of town that was hit hardest by the hurricane, and still lies mostly in ruin. This couple had videotaped their experience of making it through the storm itself (they had no car and could not evacuate). The first 15 minutes of Trouble the Water is cut together from this high-8 videotape footage. As I watched this sequence, I couldn't help but think "Thank God someone documented this." As much as I want to err on the side of having too much documentation, there is something wonderful about knowing that you are witnessing the only account of something, that you are holding, in your hand, the only photograph of that moment in time. There is something satisfying about having very little.

Sunday, May 31, 2009

On Assignments

It's been a little over two months since I turned in my BIG ASSIGNMENT, my non-fiction thesis, a project which I worked on for a year. During that year, I did absolutely no other creative writing. When I was finally finished, I was concerned that I would have trouble writing about anything else for a very long time.

In an attempt to fight the blank page, here in my final quarter at Northwestern (which, along with my college career, is very nearly over) I enrolled in one 200-level creative non-fiction course and another 200-level fiction course. Much to my surprise, I've found that I still have a few fresh ideas in my head; more, in fact, than I have ever had before. I've discovered, along the way, another little oddity that I think sets fiction apart from creative non-fiction: the usefulness of short assignments.

For my 200-level non-fiction class, we have written five short essays of about 1000 words, each in response to a designated assignment or prompt. I felt very skeptical about these assignments at the beginning of the quarter. In my mind, I had just finished a 17,000-word piece; why couldn't I be trusted to come up with my own idea for essays? Assignments, I think I thought, were for amateurs without fresh ideas. (Of course, I had used my only good idea on the 17,000-word piece, and had no new ideas at my immediate disposal. Still, I was on my high prosaic horse.)

Our first assignment was to go sit in a public space (but NOT a coffee shop) for thirty minutes, observe, and write about it. Jeebus, I thought, is there any less original non-fiction assignment than this? That Saturday evening I waddled down to a local bar called The Long Room with some friends and completed my "observation." If I have to do this stupid assignment, I thought, I may as well have an icy cold pint of Point Ale in my hand.

And then something funny happened: I walked home, scribbled a few notes down in a journal before bed, got up the next morning, wrote a first draft and... really liked it. What's more, other people read it and liked it. And I never would have written it if it weren't for that assignment.

But maybe it was just a fluke. Surely, the next assignment, in which we were to use a narrative mode that was (for at least a portion of the essay) outside of reality, would prove itself a pointless and uninspired exercise. So I wrote what turned out to be a piece about my relationship with my oldest brother, and, sure as shit, I liked that one, too. Now, at the end of the quarter, I have five short essays, each with at least a bit of potential, and none of which I would have even thought to write if it weren't for an assignment.

On the other hand, in my fiction class, we had to write one short story of anywhere from eight to twenty pages. Other than those very loose page guidelines, there was no assignment or prompt to follow when writing our stories. I had an idea rolling around in my head for a couple weeks, wrote it down, and was surprised to find it didn't suck. I'd say I like that short story draft as much as my first non-fiction assignment.

In the weeks before our short story was due, we were asked to write a few sample scenes. In these cases, there were specific guidelines to follow. In one scene, we had to write a page or two about a character who is doing something that appears villainous, but turns out to be heroic (or vice versa). In another assignment, we were to write a scene and establish some sort of major conflict between two characters as quickly as possible.

I've already forgotten what I wrote for either of these short fiction assignments. What came out on the page was formulaic, boring, uninspired crap.

I've been thinking about this for awhile: why were assignments so useful and inspiring for my creative non-fiction writing, and so distracting and constrictive for my fiction writing? I'm sure that this isn't true for everyone; after all, every instructional writing book I've ever purchased, whether dealing with fiction or non-fiction, is chocked full of assignments to inspire the writer. Some fiction writers must find prompts useful. Still, I think assignments are inherently more useful for non-fiction.

Maybe it has something to do with the way that we find our stories. When I get an idea to write a non-fiction piece, it's usually because I'm looking at something outside of myself. I hear about someone doing something interesting, or something interesting happens to me, and I think, oh, I'll write about that. Non-fiction, for me, is about what comes to me from the external world. When I get an idea to write a fiction piece, it's usually because I've dreamed up some royally fucked-up situation for a character to be in, and then dream up how the fucked-up situation concludes, and then think about connecting the beginning to the end. So fiction, for me, is about what comes from me.

I don't know if any of the above paragraph is actually true.

What are your thoughts?

In an attempt to fight the blank page, here in my final quarter at Northwestern (which, along with my college career, is very nearly over) I enrolled in one 200-level creative non-fiction course and another 200-level fiction course. Much to my surprise, I've found that I still have a few fresh ideas in my head; more, in fact, than I have ever had before. I've discovered, along the way, another little oddity that I think sets fiction apart from creative non-fiction: the usefulness of short assignments.

For my 200-level non-fiction class, we have written five short essays of about 1000 words, each in response to a designated assignment or prompt. I felt very skeptical about these assignments at the beginning of the quarter. In my mind, I had just finished a 17,000-word piece; why couldn't I be trusted to come up with my own idea for essays? Assignments, I think I thought, were for amateurs without fresh ideas. (Of course, I had used my only good idea on the 17,000-word piece, and had no new ideas at my immediate disposal. Still, I was on my high prosaic horse.)

Our first assignment was to go sit in a public space (but NOT a coffee shop) for thirty minutes, observe, and write about it. Jeebus, I thought, is there any less original non-fiction assignment than this? That Saturday evening I waddled down to a local bar called The Long Room with some friends and completed my "observation." If I have to do this stupid assignment, I thought, I may as well have an icy cold pint of Point Ale in my hand.

And then something funny happened: I walked home, scribbled a few notes down in a journal before bed, got up the next morning, wrote a first draft and... really liked it. What's more, other people read it and liked it. And I never would have written it if it weren't for that assignment.

But maybe it was just a fluke. Surely, the next assignment, in which we were to use a narrative mode that was (for at least a portion of the essay) outside of reality, would prove itself a pointless and uninspired exercise. So I wrote what turned out to be a piece about my relationship with my oldest brother, and, sure as shit, I liked that one, too. Now, at the end of the quarter, I have five short essays, each with at least a bit of potential, and none of which I would have even thought to write if it weren't for an assignment.

On the other hand, in my fiction class, we had to write one short story of anywhere from eight to twenty pages. Other than those very loose page guidelines, there was no assignment or prompt to follow when writing our stories. I had an idea rolling around in my head for a couple weeks, wrote it down, and was surprised to find it didn't suck. I'd say I like that short story draft as much as my first non-fiction assignment.

In the weeks before our short story was due, we were asked to write a few sample scenes. In these cases, there were specific guidelines to follow. In one scene, we had to write a page or two about a character who is doing something that appears villainous, but turns out to be heroic (or vice versa). In another assignment, we were to write a scene and establish some sort of major conflict between two characters as quickly as possible.

I've already forgotten what I wrote for either of these short fiction assignments. What came out on the page was formulaic, boring, uninspired crap.

I've been thinking about this for awhile: why were assignments so useful and inspiring for my creative non-fiction writing, and so distracting and constrictive for my fiction writing? I'm sure that this isn't true for everyone; after all, every instructional writing book I've ever purchased, whether dealing with fiction or non-fiction, is chocked full of assignments to inspire the writer. Some fiction writers must find prompts useful. Still, I think assignments are inherently more useful for non-fiction.

Maybe it has something to do with the way that we find our stories. When I get an idea to write a non-fiction piece, it's usually because I'm looking at something outside of myself. I hear about someone doing something interesting, or something interesting happens to me, and I think, oh, I'll write about that. Non-fiction, for me, is about what comes to me from the external world. When I get an idea to write a fiction piece, it's usually because I've dreamed up some royally fucked-up situation for a character to be in, and then dream up how the fucked-up situation concludes, and then think about connecting the beginning to the end. So fiction, for me, is about what comes from me.

I don't know if any of the above paragraph is actually true.

What are your thoughts?

Saturday, March 28, 2009

The Right Way to Tell a Story

On Tuesday, I picked up a copy of Norman Mailer's The Executioner's Song. It has been on my reading list for a while. For those that don't know, TES, which won Mailer the 1980 Pulitzer Prize, tells the story of Gary Gilmore, who was convicted of two homicides in Utah and executed in 1977.

Mailer's approach to the material is truly exhaustive. On the cover of my copy, there is a blurb from Joan Didion: "The big book that no one but Mailer could have dared." It is, indeed, a big book; massive, even. The version I bought is just over 1000 pages - large pages, small font. Mailer wrote the book based entirely from interviews he had done with those involved in Gilmore's life. The level of detail is astounding; I had to wait 200 pages before Gilmore commits his first murder. At this point, I'm about 350 pages in and I have yet to arrive at Gilmore's trial.

Which leads one to think: TES must be the single, definitive account of the Gilmore case. What writer would dare to write another book about Gary Gilmore after Mailer, one of the greatest American writers, has covered every corner, scouted every tiny crevice, squeezed every last drop of literary worth out of this juicy grapefruit of a story?

But another writer has dared. In 1995, Mikal Gilmore, writer and senior contributing editor for Rolling Stone, and perhaps more notably, the younger brother of Gary Gilmore, published Shot in the Heart, his memoir of his life with his dysfunctional Mormon family and his brother's execution. The memoir may not have earned Mikal Gilmore a Pulitzer, but it was widely critically acclaimed, and won the LA Times Book Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

I bought TES on the same day that I delivered my Creative Non-Fiction senior thesis to the people that I wrote about, Al and Mary Ann, whose 18-year-old son Jeff was murdered in a random act of violence over six years ago (still unsolved). I was pretty (read: extremely) nervous about handing it over to them. I felt I had done well on my thesis, but I had always doubted my ability to really get to the heart of their story. I didn't know Al and Mary Ann before I met them for our first interview, and since then I've only spent a total of 15-20 hours with them. We've said a lot in that time, and in certain ways I'd say I'm closer to them now than some people I've known for years. But how well can I really know them? I'm a 25-year-old, single dude. What in the hell do I know about being a parent, let alone being the parent of a murdered child?

My own insecurities aside, we had a pretty open talk about their story, and about storytelling in general. It's always hard to explain to someone just what "Creative Non-Fiction" is, so I told them that my thesis was meant to be more than a retelling of facts (which I told them from the outset) that it might not be what they expected when we first started, and that it wasn't necessarily what I had in mind when I began to write about them (which was true).

One of the reasons that it has felt so important to me to get their story "right" is because Al and Mary Ann have had to deal with a number of cases where people have gotten their stories wrong - namely, reporters confusing facts, mistakenly reporting Jeff as a gang member, etc., etc. In fairness, Jeff's case and Al and Mary Ann's subsequent experience is incredibly complicated, including a not-so-happy relationship with local police and politicians. Al himself has told me that he himself once wanted to write a book about their experience (if for no other reason, I think, than to set the record straight on a few things).

At one point during our talk, Mary Ann confided that she has always thought that if anyone was going to tell their story the "right" way, it would be herself and Al (adding, at the same time, that it would be interesting to see an outsider's take on the matter). At that point, I assured them that no matter how I wrote about their story, it in no way meant they couldn't also write it.